- Name

- Accelerated Expertise

- Author

- Robert R. Hoffman

- Paul Ward

- Paul J. Feltovich

- Lia DiBello

- Stephen M. Fiore

- Dee H. Andrews

- Pages

- 256

- Date Published

- 2013-08-15

- Date Read

- 2023-12-29

- Bookshelves

- Have Read

- Favorites

- Genres

- Business

Summary

This book deals with current issues of training:

- How to quicken the training process while maintaining its effectiveness (Rapidized Training),

- How to train more quickly to higher levels of proficiency (Accelerated Proficiency),

- How to conduct cognitive task analysis more efficiently to feed into training (Rapidized Cognitive Task Analysis),

- How to rapidize the sharing of lessons learned from the battlespace into the training context (Rapidized Transposition), and

- How to ensure that training has a stable and lasting effect (Facilitated Retention).

Research findings

One must be cautious in generalizing the effects of the numerous interacting variables that affect training. “Training for complex tasks is itself a complex task and most principles for good instruction are contextual, not universal” (Reigeluth, personal communication). Some general findings are:

Training

- Training is generally more effective if the initial learning is about domain concepts and principles and not just specific details of tasks and procedures.

- Training at advanced levels (training to perform in dynamic and complex domains where tasks are not fixed) is generally more effective if it involves extensive practice on realistic examples or scenarios (problem-based learning).

- Training has to balance giving and withholding of outcome and process feedback to achieve optimal learning at different stages of advancement.

- Training at intermediate and advanced levels benefits significantly from experience at challenge problems or cases; the “desirable difficulties.” Short-term performance might suffer, but longer-term gains will emerge.

- Mentoring is valuable and critical for advanced learning, because it provides opportunities to receive rich process and outcome feedback as learners encounter increasingly complex problems. However, mentoring is not always necessary in advanced stages of learning.

- Training using intelligent tutoring systems and serious games (virtual reality systems) can be highly effective.

- Training that is based on a dynamic, context-sensitive, and situation-specific model derived from cognitive task analyses of expert performers is more effective than legacy training programs.

Transfer

- Initial learning that is more difficult can lead to greater flexibility and transfer; when learners are initially exposed to simplifications of complex topics, serious misunderstandings can remain entrenched and interfere with or preclude deeper, more accurate understandings.

- Transferring a skill to new situations is often difficult but can be promoted by following a number of training principles: employing deliberate practice, increasing the variability of practice, adding sources of contextual interference, using a mixed practice schedule, distributing practice in time, and providing process and outcome feedback in an explicit analysis of errors.

Retention and Decay

- Significant decay can occur even within relatively short time frames (days to weeks) for any form of skill or learned material. Although there can be differential decay of memory versus skill, decay is generally greatest shortly after a hiatus period begins, and levels out thereafter. For example, pilots know that most skill loss occurs within the first year, and then skill decay slows marginally after that.

- The best predictor of skill retention at the end of a hiatus is the level of performance achieved (including overlearning) just prior to the hiatus. The greater the degree of overlearning, the more that the decay curve gets “stretched out.”

- Performance that requires appreciable coordination between cognitive skills and motor skills is most substantially degraded (again, using piloting as an example, instrument flying skills deteriorate more than basic flying skills).

- Periodic practice during periods of hiatus should commence not long after the hiatus begins. Periodic practice can promote retention over long intervals.

- Retention during hiatus is better if the same practice task is not repeated, but is interspersed with other job-related tasks within practice sessions.

- The variable having the greatest impact on performance after a retention interval is the similarity of the conditions of the training (acquisition) and work (retention) environments. To promote retention, there should be substantive and functional similarity of the job tasks and job environment with the retention tasks and task environment.

Teams

- Individuals who are more proficient at solving problems related to the team’s primary goals (team task work) place a high value on cooperation and engage in more work-related communication (teamwork). Thus, training in the achievement and maintenance of common ground will enhance team performance.

- In high-performing teams, team members develop rich mental models of the goals of the other team members. Training that promotes cross-role understanding facilitates the achievement of high proficiency in teams.

- High-performing teams effectively exchange information in a consensually agreed- upon manner and with consistent and meaningful terminology, and are careful to clarify or acknowledge the receipt of information. Training that promotes such communication facilitates the achievement of high proficiency in teams.

- Experienced teams efficiently exchange information, and may actually communicate overtly less than teams that are not high performing.

- Experience while team membership changes can facilitate the acquisition of teamwork skills.

- The question of performance decay in teamwork skills due to hiatus is an open subject for research.

- Training for accelerated team proficiency, like training for individuals, benefits from problem or scenario-based practice using realistic and complex scenarios (e.g., serious games, simulated distributed mission operations).

None of the above generalizations holds uniformly; for all of the above, one can find studies showing opposite effects, or no effects. For example, while it makes sense to maintain consistency of team membership, the mixing of teams can allow team members to gain skill at adapting, and skill at the rapid forging of high-functioning teams. In addition, in many work contexts (including the military), membership can be necessarily ad hoc, there is a mixture of proficiency levels, and team membership typically changes frequently.

Figures

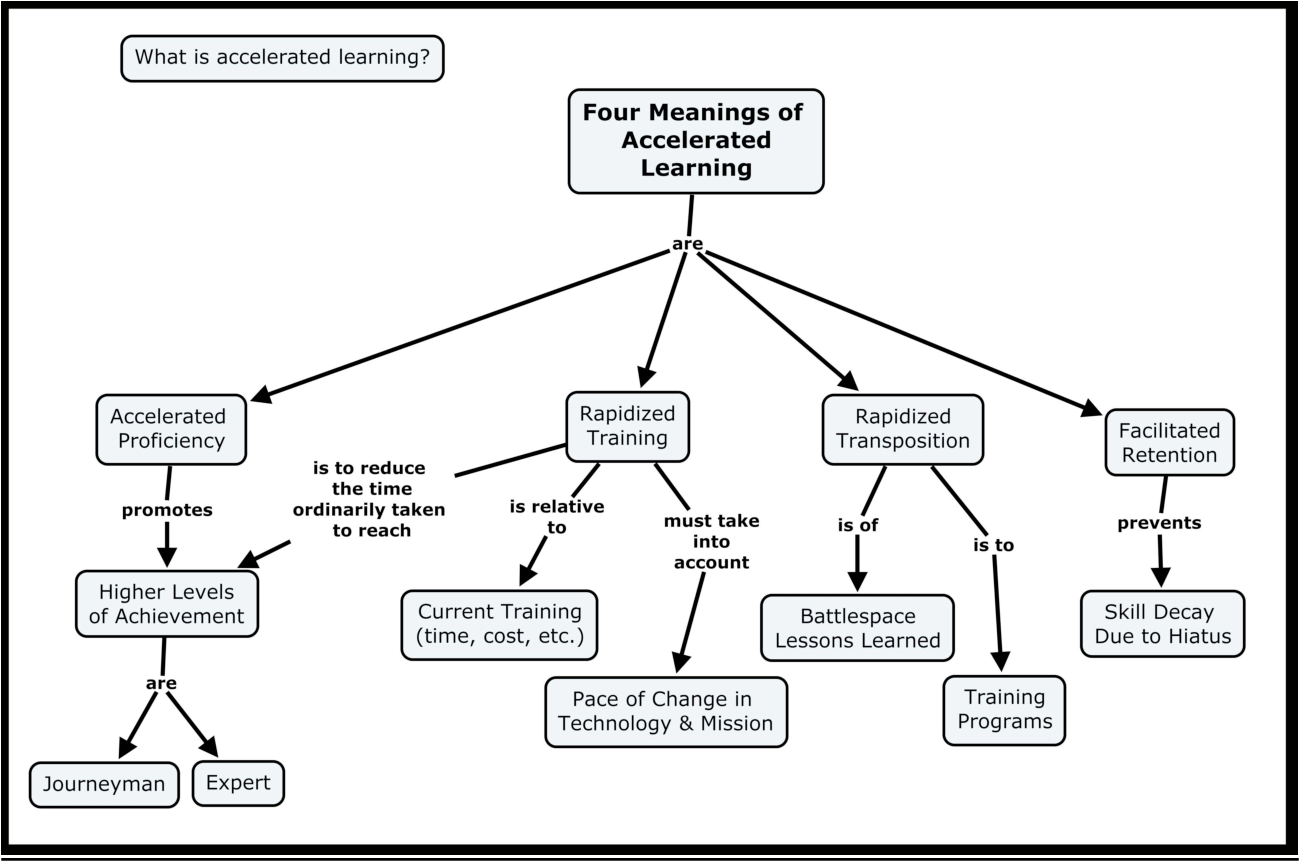

This is actually figure 1.1 from DOI:10.21236/ada536308 Hoffman, R.R., Feltovich, P.J., Fiore, S.M., Klein, G., Missildine, W., & DiBello, L. (2010). Accelerated Proficiency and Facilitated Retention: Recommendations Based on an Integration of Research and Findings from a Working Meeting.

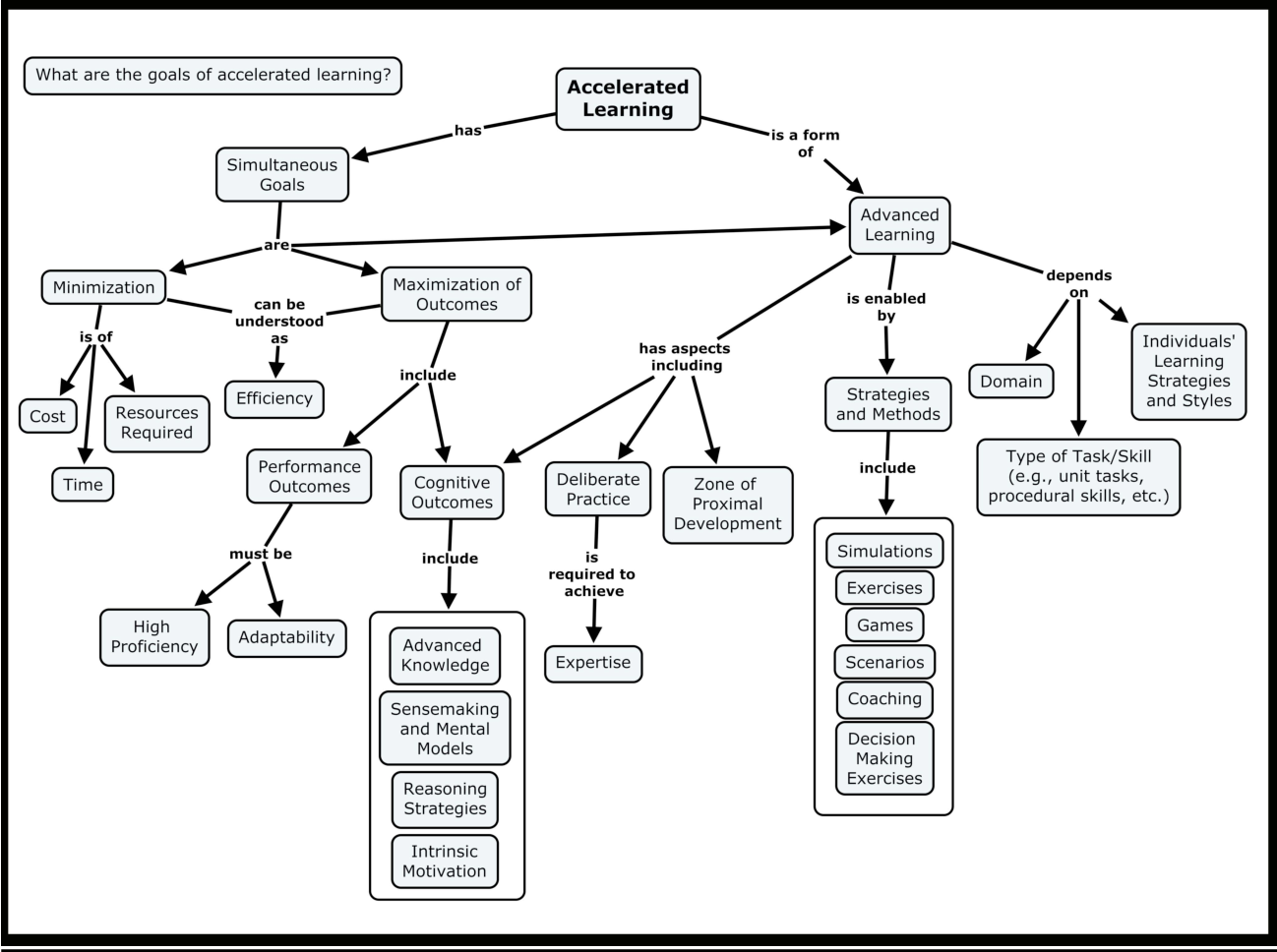

This is actually figure 1.2 from DOI:10.21236/ada536308 Hoffman, R.R., Feltovich, P.J., Fiore, S.M., Klein, G., Missildine, W., & DiBello, L. (2010). Accelerated Proficiency and Facilitated Retention: Recommendations Based on an Integration of Research and Findings from a Working Meeting.

Tables

| The expert is highly regarded by peers. |

| The expert’s judgments are accurate and reliable. |

| The expert’s performance shows consummate skill (i.e., more effective and/or qualitatively different strategies) and economy of effort (i.e., more efficient). |

| For simple, routine activities, experts display signs of “automaticity” where the expert seems to be carrying out a task without significant cognitive load and conscious processing is reserved for strategic control and/or more complex activities. |

| The expert possesses knowledge that is fine-grained, detailed and highly organized. |

| The expert knows that his knowledge is constantly changing and continually contingent. |

| The expert forms rich mental models of cases or situations to support sensemaking and anticipatory thinking. |

| The expert is able to create new procedures and conceptual distinctions. |

| The expert is able to cope with rare and tough cases. |

| The expert is able to effectively manage resources under conditions of high stakes, high risk and high stress. |

| Typically, experts have special knowledge or abilities derived from extensive experience with subdomains. |

| The expert has refined pattern perception skills and can apprehend meaningful relationships that non-experts cannot. |

| Experts are able to recognize aspects of a problem that make it novel or unusual, and will bring special strategies to bear to solve “tough cases.” |

| 1. Practitioners at this level have knowledge that is declarative or propositional;, their reasoning is said to be explicit and deliberative. Problem solving focuses on the learning of facts, deliberative reasoning, and a reliance on general strategies. |

| 2. The declarative knowledge of practitioners at this level has become procedural and domain-specific. They can automatically recognize some problem types or situations. |

| 3. At this level, procedures become highly routinized. |

| 4. These practitioners are proficient and have a great deal of intuitive skill. |

| 5. Practitioners at this highest level can deliberately reason about their own intuitions and generate new rules or strategies (what Dreyfus and Dreyfus call “deliberative rationality”). |

| Naïve: One who is ignorant of a domain. |

| Novice: Literally, someone who is new—a probationary member. There has been some (“minimal”) exposure to the domain. |

| Initiate: Literally, someone who has been through an initiation ceremony—a novice who has begun introductory instruction. |

| Apprentice: Literally, one who is learning—a student undergoing a program of instruction beyond the introductory level. Traditionally, the apprentice is immersed in the domain by living with and assisting someone at a higher level. The length of an apprenticeship depends on the domain, ranging from about one to 12 years in the craft guilds. |

| Journeyman: Literally, a person who can perform a day’s labor unsupervised, although working under orders. An experienced and reliable worker, or one who has achieved a level of competence. It is possible to remain at this level for life. |

| Expert: The distinguished or brilliant journeyman, highly regarded by peers, whose judgments are uncommonly accurate and reliable, whose performance shows consummate skill and economy of effort, and who can deal effectively with certain types of rare or “tough” cases. Also, an expert is one who has special skills or knowledge derived from extensive experience with subdomains. |

|

Method |

Yield |

Example |

|

In-depth career interviews about education, training, etc |

Ideas about breadth and depth of experience; estimate of hours of experience. |

Weather forecasting in the armed services, for instance, involves duty assignments having regular hours and regular job or task assignments that can be tracked across entire careers. Amount of time spent engaged in actual forecasting or forecasting-related tasks can be estimated with some confidence (Hoffman, 1991). |

|

Professional standards or licensing |

Ideas about what it takes for individuals to reach the top of their field. |

The study of weather forecasters involved senior meteorologists from the US National Atmospheric and Oceanographic Administration and the National Weather Service (Hoffman, Coffey, & Ford, 2000). One participant was one of the forecasters for Space Shuttle launches; another was one of the designers of the first meteorological satellites. |

|

Measures of performance at the familiar tasks |

Can be used for convergence on scales determined by other methods. |

Weather forecasting is again a case in point since records can show for each forecaster the relation between their forecasts and the actual weather. In fact, this is routinely tracked in forecasting offices by the measurement of “forecast skill scores” (see Hoffman, Trafton, Roebler & Mogil, in preparation). |

|

Social Interaction Analysis |

Proficiency levels in some group of practitioners or within some community of practice (Mieg, 20001 Stein, 1997). |

In a project on knowledge preservation for the electric power utilities (Hoffman & Hanes, 2003), experts at particular jobs (e.g., maintenance and repair of large turbines, monitoring and control of nuclear chemical reactions, etc) were readily identified by plant managers, trainers, and engineers. The individuals identified as experts had been performing their jobs for years and were known among company personnel as “the” person in their specialization: “If there was that kind of problem I’d go to Ted. He’s the turbine guy.” |

| Novice | 10-45 Lifespan (age): Learning can commence at any age → → → (e.g., the school-age child who is avid about dinosaurs; the adult professional who undergoes job re-training) | 45-60+ Lifespan (age): Achievement of expertise in significant domains may not be possible | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intern and apprentice | 10-20 Lifespan (age): Individuals less than 18 years of age are rarely considered appropriate as apprentices | 20-55 Lifespan (age): Can commence at any age → → → | 55-60+ Lifespan (age): Achievement of expertise in significant domains may not be possible |

| Journeyman | 15-30 Lifespan (age): It is possible to achieve journeyman status (e.g., chess, computer hacking, sports) | 30-60+ Lifespan (age): Is typically achieve in mid- to late-20s, but development may go no further | |

| Expert | 15-35 Lifespan (age): It is possible to achieve expertise (e.g., chess, computer hacking, sports) | 35-60+ Lifespan (age): Most typical for 35 years of age and beyond | |

| Master | 25-35 Lifespan (age): Is rarely achieved early in a career | 35-50 Lifespan (age): Is possible to achieve mid-career | 50-60+ Lifespan (age): Most typical of seniors |

|

Apprentice |

Journeyman |

Expert |

Senior Expert |

|

| Process |

Forecasting by extrapolation from the previous weather and forecast and by reliance on computer models |

Begins by formulating the problem of the day but focuses on forecasting by extrapolation from the previous weather and forecast and by reliance on computer models |

Begins by formulating the problem of the day and then building a mental model to guide further information search |

Begins by formulating the problem of the day and then building a mental model to guide further information search |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy |

Reasoning is at the level of individual cues within data types |

Reasoning is mostly at the level of individual cues, some ability to recognize cue configurations within and across data types |

Reasoning is in terms of both cues and cue configurations, both within and across data types. Some recognition-primed decision-making occurs |

Process of mental model formation and refinement is more likely to be short-circuited by recognition-primed decision-making skill |

| Static versus dynamic |

Are important aspects of a situation captured by a fixed “snapshot,” or are the critical characteristics captured only by the changes from frame to frame? Are phenomena static and scalar, or do they possess dynamic vector characteristics? |

|---|---|

| Discrete versus continuous |

Do processes proceed in discernible steps, or are they unbreakable continua? Are attributes describable by a small number of categories (e.g., dichotomous classifications like large/small), or is it necessary to recognize and utilize entire continuous dimensions (e.g., the full dimension of size) or large numbers of categorical distinctions? |

| Separable versus interactive |

Do processes occur independently or with only weak interaction, or is there strong interaction and interdependence? |

| Sequential versus simultaneous |

Do processes occur one at a time, or do multiple processes occur at the same time? |

| Homogeneous versus heterogeneous |

Are components or explanatory schemes uniform (or similar) across a system—or are they diverse? |

| Single versus multiple representations |

Do elements in a situation afford single (or just a few) interpretations, functional uses, categorizations, and so on, or do they afford many? Are multiple representations (e.g., multiple perspectives, schemas, analogies, case precedents, etc) required to capture and convey the meaning of a process or situation? |

| Mechanism versus organicism |

Are effects traceable to simple and direct causal agents, or are they the product of more system-wide, organic functions? Can important and accurate understandings be gained by understanding just parts of the system, or must the entire system be understood for even the parts to be understood well? |

| Linear versus nonlinear |

Are functional relationships linear or nonlinear (i.e., are relationships between input and output variables proportional or non-proportional)? Can a single line of explanation convey a concept or account for a phenomenon, or are multiple overlapping lines of explanation required for adequate coverage? |

|

Content-to-content |

Applying knowledge in one content domain to aid the learning of knowledge in some other content domain. |

|

Procedure-to-procedure |

Using procedures learned in one skill area to work out problems in some other skill area. |

|

Declarative knowledge-to-procedural knowledge |

Book knowledge or knowledge of concepts and principles learned about an area aids in the learning of skills, strategies or procedures in that same area. |

|

Procedural knowledge-to-declarative knowledge |

Experience with the skills, strategies or procedures in an area aids in the learning of conceptual knowledge in that same area. |

|

Transfer of self-aware strategic knowledge |

Knowledge about one’s own reasoning or strategies is applied from the original domain of learning to some other domain. |

|

Cross-subdomain transfer of declarative knowledge |

Knowledge of a concept or cause is generalized across subdomains (e.g., lightning as a form of electricity). |

|

Cross-subdomain generalization (also called vertical transfer) |

Knowledge of a particular is generalized across subdomains (e.g., learning about the cause of a particular war facilitates learning about the causes of war in general). |

|

Cross-domain transfer of declarative knowledge |

This includes transfer based on analogy. It also includes the “usefulness of useless knowledge,” as in trivia quizzes. |

|

Lateral transfer of skill |

Learning one perceptual motor skill facilitates the learning of some other very similar perceptual motor skill (e.g., ice skating and roller skating). |

| Transfer tasks | Expectation based on common elements theory | Actual outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Aircraft piloting to UAV piloting. | Positive transfer due to there being many common elements. | Negative transfer. The reason is because of one simple but crucial difference (angle of approach versus angle of view during landing). |

| Learning gun range safety rules and procedures using M-15, then demonstrating knowledge of those safety rules at the pistol range. | Positive transfer due to there being many common elements. | Large negative transfer. Again, one simple but crucial difference: muzzle length. Rifles “afford” laying the gun down with muzzle pointed downrange. |

| Piloting the B-52 then navigating on the B-1. | Negative transfer because there are major changes in task, and differences in the planes (flight characteristics, avionics, etc). | Postive transfer. Confidence was the trump card (see text). |

| Judging the breeding quality of pigs and cattle based on pictures versus based on a list of the important variables. | Positive transfer due to there being many common elements that enter into the judgments—the judgments made (loin length, breeding quality, etc) are the same. | Change in the task resulted in change in the reasoning strategy though the basic task goal was the same (see text). |

| Rodeo riding versus tournament jousting. | Positive transfer due to common elements of horse riding. Both activities require skill at falling off a horse without injury, for instance. | Large negative transfer because rodeo riders have a habit of looking toward the rear of the horse upon exiting the gate; this habit disadvantages them in jousting. |

| Learning to estimate the area of rectangular pieces of paper versus pieces of other shapes (e.g., triangles, parallelograms). | Positive transfer due to the shared task. | No positive transfer. Performance for rectangles is better than for other shapes. |

| The scenarios are tailored to learners (individual and/or group), depending on level of achievement, preparedness, or other factors. |

| Scenarios are created from lessons learned. |

| Scenario training assumes high intrinsic motivation of the trainee to work hard, on hard problems. |

| For any given level of training, the scenarios are tough. They are novel to the learner, challenging them in ways described by Cognitive Flexibility Theory and Cognitive Transformation Theory (see above). |

| Typically there is some daunting adversary, such as a superior or more capable opposing agent or force. |

| The trainee is challenged to learn to think like the adversary. |

| The fidelity is as high as needed. (In order: desktop exercises using paper and pen, virtual worlds presented on computer monitors, virtual environments, very high fidelity simulators, simulated villages.) |

| Scenarios mimic the operational context. |

| There is a designed-in ability for observers to record and measure what happened. |

| The observers are experts. |

| There are multiple reviews, not just one single “after action” review (although the latter is highly effective). |

| Reviews provide both outcome and process feedback. |

| Reviews include retrospection and the analysis of decision processes, emotional state of mind, teamwork, mental projection to the future, and other macrocognitive processes. |

| The goal is for trainees to acquire strategic knowledge, adaptability and resilience. |

| The policy-proficiency paradox. In some domains (e.g., intelligence analysis, cultural understanding) broad knowledge is a requirement. Promotion to leadership positions depends on having had experience in diverse jobs/roles. But this policy limits the opportunity for individuals to achieve high levels of proficiency in any one job/role. |

| The culture-measurement clash. In some domains, performance has to be continually evaluated even after the achievement of ceiling-level performance according to some criterion. Research has shown that experts continue to get better even after they “always get it right” on some criterion measure of performance. Furthermore, once a fighter pilot, for instance, has achieved very good performance as evaluated at some stage of training or operational performance, they will maintain that level, on the record, because if they do not they will not advance in their military career. This sets up a possible goal conflict, where in some domains or organizations there might actually be incentives against measuring (and thereby understanding) proficiency and its development. |

| The myth of the career path. Careers are not set on a specific path in the sense of tracking a standardized progression plan. “While there is a written path, it is rarely followed.” Careers are managed within sets of changing constraints, especially “bellybutton shortages.” In some specialties (e.g., piloting) there is a sophisticated process for managing careers. In most specialties, there is not. “You can select your preferences for future assignments, but your commander also makes recommendations and then the personnel office decides, depending on needs, billets available, etc.” In some careers, time away from the specialty is not tracked so you do not know when to add reintegration training. |

| The irony of transitioning. Promotion hinges on broad experience that helps develop competency at jobs/ roles that fall at supervisory levels. But assignments (in the military) will transition individuals across levels. Just-in-time training courses are out there, but are not designed for people transitioning across levels. Training is necessary prior to any reassignment, and while the courses (typically two months long) can be good for exposure, they do not promote deep comprehension. There is not enough time available. There is no tracking of people who can help in training. It can be awkward to ask for help from subordinates. |

| The ironies of demotivation. Demotivation manifests itself in a number of forms and for a variety of reasons. Deployment itself contributes to the acceleration of proficiency, but the basic job responsibilities can consume one’s time and energy. There is significant burnout potential for doing extra learning and training. Broadening negatively impacts career progression and triggers thoughts of getting out. “You repeatedly experience a loss of confidence.” |

| The ironies of reassignment. Reassigning individuals just as they achieve high proficiency cuts against the notion that organizational capability is built upon individual expertise. Reassignment may be necessary for staffing, and is necessary for training individuals who are selected to move to higher levels of work. But it can be recognized that reassignment is at least partly responsible for creating the problem of skill decay in the first place. There are significant secondary effects that also should be considered. For example, upon return to a primary assignment, the post-hiatus refresher training might involve work on routine cases. This may lead to overconfidence in the earliest stage of a redeployment, and might limit the worker’s ability to cope with novel or challenging situations. |

| The ironies of under-utilization of resources. While some organizations recognize the need to collect and share “lessons learned,” such lessons are often archived in ways that make meaningful search difficult, and hence become “lessons forgotten.” Debriefing records are a significantly under-utilized resource for training, and could provide a library of cases, lessons learned, and scenarios for use in formative training. |

| The irony of the consequences of limiting the resources. In past years, re-training following hiatus could be brief (six weeks) (we might say “accelerated”) because pilots had had thousands of hours of flying time prior to their hiatus. But pilots are flying less now, largely due to high cost. This has two repercussions: it mandates more training post-hiatus (which has its own associated costs) and the reduced flight practice hours detract from the goal of accelerating the achievement of proficiency, thus placing the overall organizational capability at risk. |

| Core syllogism |

|

|---|---|

| Empirical ground |

|

| Additional propositions in the theory |

|

| Core syllogism |

|

|---|---|

| Empirical ground and claims |

|

| Additional propositions in the theory |

|

|

|

| Core |

|

Figure 15.1 Possible proficiency achievement and acceleration curves

Figure 15.2 A notional roadmap for studies on accelerated proficiency and facilitated retention (CTA = Cognitive Task Analysis)